Goths, Visigoths, Ostrogoths, Vandals, Francs… these were frugal men who nourished on milk, cheese and small amounts of meat.

The people who had been invaded left the towns and took refuge in the countryside, where dairy products constituted a large part of their diet.

The Early Middle Ages had other preoccupations other than the supply of cheese, it is not until the second half of the 8th Century that the Western Carolingian Empire, with the accession of the grand emperor, that it was mentioned.

By chance, some Benedictine monasteries conserved the precious knowledge of how cheese was made, a knowledge which passed through the ages. The monk, Einhard from Saint Gall, who was the historian and secretary of Charlemagne at the end of his life, told of some anecdotes.

One of these anecdotes, in reference to the value of which the Emperor gave to the cheese and gave a memorable account: during one of his trips, the Emperor had arrived unexpectedly at the house of a poor bishop, on a day without meat, so the emperor had to do with some bread and cheese. The cheese had green marks which he had never seen before, so he removed them with his knife. His host, the bishop respectfully told the emperor that he was removing the best part of the cheese. Charlemagne listened to the bishop’s advice and was soon convinced, so much so that he asked his host to send him two cases of the cheese each year to Aix-le-Chapelle.

Unfortunately, Einhard did not mention where this happened, however it was probably Vabres, a small village close to Roquefort; where there was an important abbey where the most reverend abbot, although not the bishop, was mitred, and received passing important guests by tradition.

But Einhard does specify that after three years, Charlemagne took pity on the unfortunate prelate who had to travel the country in search of good cheeses and bring them back to the emperor in big enough quantities.

Einhard also wrote, in the year 774: “Charlemagne, returning from Italy where he had beaten the Lombardi, stopped at the priory of Reuil-el-Brie. There, the prior showed them the cellars where there were some marvellous Brie cheeses, which he had personally put out for the tithe. Of which the emperor and his men tasted copious amounts.

“I thought I knew everything about what I ate,” said Charlemagne, “It was only vanity on my part; I am discovering one of the most marvellous dishes and ordering only twice a year a quantity of these cheeses makes me want to go to my palace in Aix-la-Chapelle.”

Georges Duby (The Rural Economy and the life in the countryside in the Medieval West) talks about the fact that in the 8th Century AD, King Ines of the Ango-Saxon kingdom of Wessex, demanded from one of the villages; “three hundred round loafs, ten sheep, ten geese, twenty chickens, ten cheeses, ten measures of honey, five saumons and one hundred eels.” Therefore, even at this time, cheese was used as a tax.

Later, the Crusaders brought a number of secrets of cheese fabrication from the Orient that they recounted to the monks who worked for the prosperity of their convents. At the time, the rule of Saint-Benoît authorised the consummation of cheese, the monks started to produce a product from which they could profit from straight away.

The Benedictines and the Cistercians especially developed the production of cheese throughout Europe. They were the origin for a number of cheeses, which are still well-known today, Pont-Evêque, Maroilles, Munster, Tête de Moine, Cîteaux, Herve and Linbourg. A cartulary of the abbey of Maroilles mentions the fee which was to be paid to the abbot in cash for cheeses, called at the time “craquegnons.”

The devastation as a consequence of the Norman invasion succeeded the reign of terror of the year 1000AD. Again, the monasteries acted as refuge for the lords and the terrified people.

For two centuries, the rate at which cheese was made faltered and it was not until the second half of the 13th Century that there was any mention of co-operative farm dairies.

The Church became more powerful than ever, due to the massive donations at the period of the terror. The abbots and the bishops became veritable feudal lords who profited from their new positions, clearing the way to form large agricultural centres.

If necessary, the religious Benedictines established pastures to rear dairy cattle; in effect, they were forced to shelter the numerous animals during the period of terror.

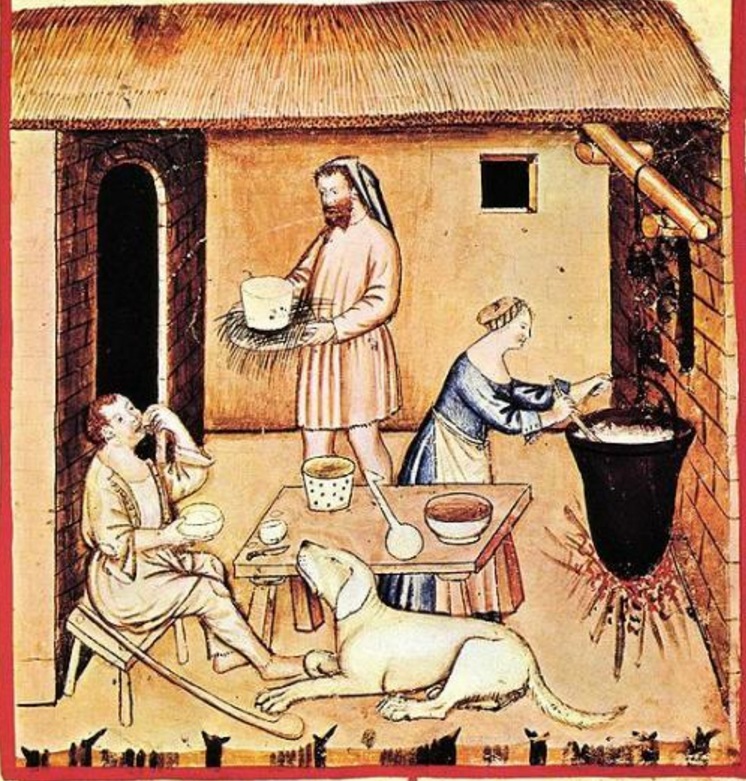

Farm cheeses appeared around the 13th Century, the women of the countryside, looking for other sources of income and a way to get the most out of the production of the milk came up with new varieties of cheese. The farmers, who were also occupied with the preparation of cheeses, also invented different varieties.

As a result, the most infamous cheeses, which are still around today; the Comté, Emmental, Gruyère and Beaufort, are all cheeses made from the collective resources of a village, which formed what are now called co-operative dairies.

The principle was as follows, twice a day, the farmers took the milk from their yield. In this way, the large quantities of milk could be used to make large gruyere cheeses, which could then be redistributed. Each farmer received the fruit of his labour.

A large quantity of cows were needed to produce a cheese which used 700 to 1000 litres all at once. These co-operative dairies grew in number at the beginning of the 13th Century. Traces show that a co-operative dairy was in place in Deservilliers, a small village of Doubs, in 1278.