Many of the techniques of production were developed empirically and often were not written down.

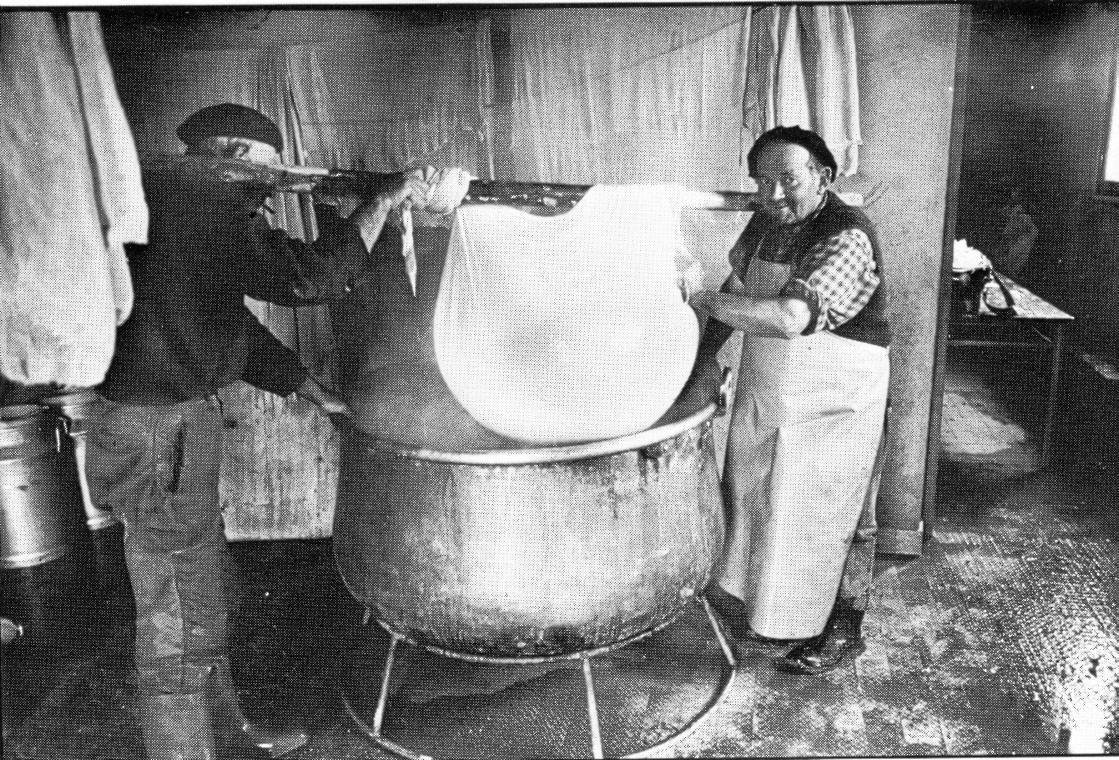

Take, for example, the helping hand of the cheese maker who puts his arms in the copper vat and pulps the morsels of the curds to quicken up the phases of production.

In Corsica, the traditionally made cheeses are dominated by micro-productions, of which the recipes are passed down by word of mouth from generation to generation or by locals.

The use of the written word can counter that which has been passed by word of mouth.

The written word seems to be the most solid gage of credibility for the experts who evaluate the technical specifications. Yet in this logic, the notion of a common legacy is raised, which often merges the historical dimension, the little stories and the notoriety, without real historical study, that has been reduced to written proof.

The problem is that the producers choose to protect their own interests. For many, it is about the protection of a place of production, the argument for the territorialisation is about the legacy. Certain organisations such as the “Chambres d’agriculture” play an active role in the legacy of the productions, and the places make up the tourist map of the region.

This context carries risks. For example, the Brique du Forez is a cheese which can be made from cow’s milk, goat’s milk or a mix of the two, and made according to techniques which vary according to the geographical altitude. These productions, made up from a number of varying associations and different places, are hard to protect. And yet, they are present in the different regions of France. Another example, the Tomme de Savoie, obtained an IGP in 1996.

From now on the producers must be in line with one specification of techniques and can no longer use the term ‘tomme de Savoie,’ where nit so long ago, there was a multitude of names and methods of productions according to the places where it was produced.

This dimension of legacy is associated with perfection, recurrence, traceability and hygiene standards. In this way measures of protection, which are difficult to carry out, have the tendency to lead to a forced legacy of the production methods, which are culturally weak, and lead to an impoverishment of the diversity of the other cheeses, where at worst others are pushed aside.

The obligation to provide proof of the precedence of a production refers to the oral and the written evidence. The ancient oral accounts have little weighting compared to written documents. Yet, a number of productions destined for consumption by those who carried them out do not carry any written traces. In our culture, the knowledge aquired from experience, passed on by ancient civilisations have less value, compared to the knowledge aquired from books. There is a necessity for the profession to agree what is proof and what isn’t without impoverishment of the practices of production.

The place of local knowledge, which is difficult to identify and write down, has the tendency to diminish. The written word makes that which would be otherwise implicit, explicit. The written rule is opposes the oral practices; it forces a choice and fixes the savoir-faire. In this way, this formalised legacy of the cheese, fixes the practices which essentially belong to the domain of oral communication. We have the tendency to move towards a form of vitrification of these productions which were multiform until now, in fixing the part which is living, evolutional and inhibiting the expansion of its potential diversity which we choose to pass on to future generations.