The history of cheese is a bit like the history of France. It crosses the paths of Charlemagne and Napoleon, combines with the religious aspects and the evolution of scientific research.

OBSERVATIONS CONCERNING THE PROJECT OF INSCRIPTION OF FRENCH GASTRONOMY TO THE IMMATERIAL HERITAGE OF HUMANITYCOMBINED WITH TO UNESCO.

CHEESE: PILLAR OF FRENCH GASTRONOMY

Closely combined with French history and its tradition, cheese is a product of the ‘terroir,’ often made in a certain geographical area according to specific, characteristic methods. It is often the place of production which gives the cheese its name. Confined to a commercialisation on the markets in proximity, unable to master the cold and transport the fragile product, the production has in effect stayed for a long time on the farms, in small volumes.

The Munster was born in 855AD in a monastery in Alsace. Its name means ‘abbey-church.’ A century later, around 960AD, another recipe was discovered in Picardy: the Evêque de Cambrai saw the monks of Thiérache to prolong the maturing of their cheese, an initiative of the famous Maroilles cheese.

According to a text of 1060AD, it is stipulated that the charges due to the abbot of Conques should be given in the form of two Roquefort cheeses. Later, in 1411, King Charles VI granted licensing letters to the inhabitants of Roquefort, who matured their in their caves since ancient times, the monopoly of this practice “that which was made since time immemorial in the caves of the said village,” the charter was confirmed by Charles VII in 1457, Henri III in 1516, François II in 1560, Louis XIII in 1619, Louis XIV in 1645 and Louis XV in 1752. Since then, the AOC was obtained in 1925 and conformed in 1973.

It is therefore all of the history of France which appears in the light of this artisan, traditional savoir faire, like a regular interaction between customs and politics.

The multiple methods of fabrication of the cheeses show the aptitude of man and how humans adapt to nature and the environment. In France, the selection of the multiple breeds of dairy cow and the eight grand families of cheese are as much a response to man and climate as to geography and sometimes geology of a region of production.

In Poitou and in Touraine, grass is rare in summer: goats have been reared since the Sarasin invasions of the 6th Century. In Normandy, the humid climate assures grass the whole year round and therefore milk. It is not necessary to conserve the cheeses very long after they are taken out of the moulds, and undergo only a short maturing process, like Camembert and Neufchâtel. When winter arrives, the maturing process is lengthened slightly , with the Pont d”Evêque and Livarot. Written about in ‘le Roman de la Rose’ in 1236, ‘angelot’ of the Pays d’Auge is the ancestre of the Pont l’Evêque, a soft cheese with a washed rind. It is also the forbearer of Livarot. The Parisian Basin, has ling since been urbanised. To supply all of the towns all year round, the cheese makers delivered varieties which were soft, like brie, partially matured. The maturing was prolonged in the limestone caves of these cheese makers, who became ‘affineurs’ and matured cheese was available in every season.

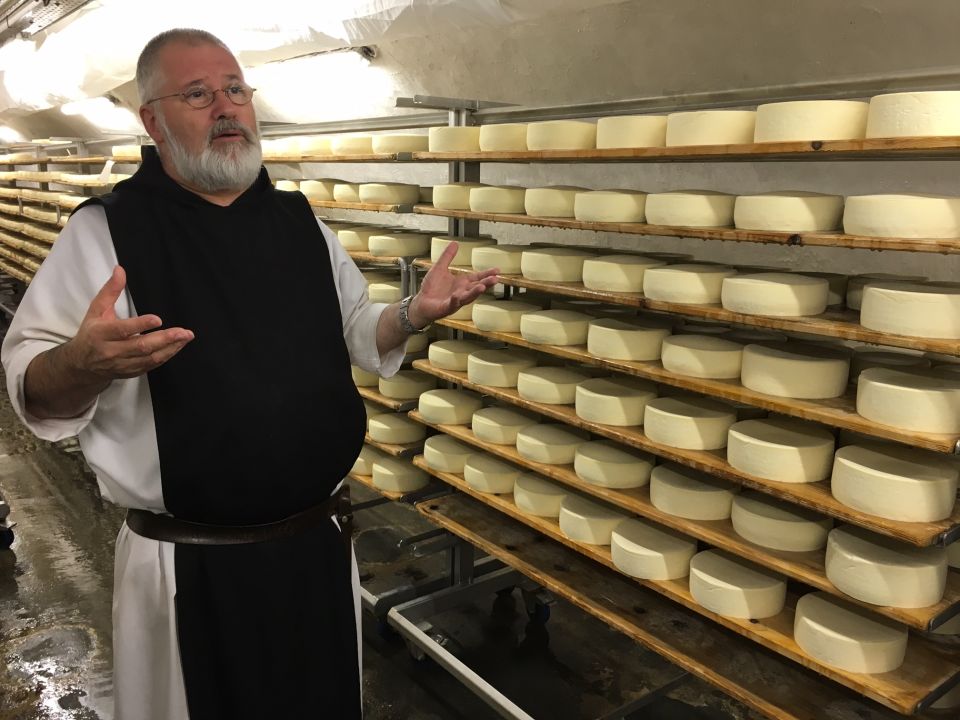

In the Massif Central ad Auvergne, the cold, snowy winters have needed the fabrication of large cheeses for 2000 years, cheeses that can be conserved for a long time, like Cantal and Laguiole. In the Pyrenees, the milk, mostly from ewes, is available in the field in spring, then in summer in the mountains. Large cheeses are made like Ossau Iraty and Bethmale which are conserved until the next spring. In the north, in Lorraine and Alsace, there isn’t much grass and therefore not much milk in winter. Cheeses were made essentially in the monasteries, and had to be conserved for the whole of winter. There are varieties which are soft, but matured for along time and with a washed rind, like the Maroilles and the Munster. In the Jura, or in the Alps, the milk is produced in the summer, on the pastures liberated from the snow. This means that enormous pressed cheeses can be made like Comté, Beaufort, Abondance etc…

These cheeses ‘de garde’ (for storing) are the biggest: they can weigh more from twenty kilos up to more than one hundred. They resist being transported and can be conserved for along time. They descended once again into the valleys in autumn, and can be kept until the following summer. From the 13th Century in France, the first dairy co-operatives were born. The farmers of certain villages of the Alps and the Jura assembled their daily collections of milk to make a large cheese. In the Mediterranean region, the ewes and the goats adopted better than the cows to the rare vegetation and hot and dry weather. The cheeses were small: Pelardon, Banon, Tomme d’Arles.

In this way, the cheeses have are related to the particular space they were made. Their link with the name of a town is combined with a history and collective practices. The local production crosses the space and the climate and makes the object of a shared savoir faire. All the cheese productions have a different history but the precedence which gives the credibility is strongly linked to the memory which is passed down.